We traveled to Taipei in the morning and packed the early afternoon with visits before meeting the bus at the hotel. Since the Confucius Temple in Kaohsiung was under construction, we got to visit a Confucius temple in Taipei instead. This temple is dedicated to the 77th grandson of Confucius. Like the Japanese monarchy, the descdants of Confucius have been tracked in an unbroken lineage and are still well-regarded today. They have been recognized by each dynasty even through changeovers. Confucius is not considered a deity, and neither is his lineage. Rather, he was such a respected teacher during his time that people today will worship his spirit and follow his teachings, but do not believe him to be something akin to a Daoist god.

The first thing we saw upon arrival was a monument with three monkeys, which represented “See No Evil”, “Speak No Evil”, and “Hear No Evil”. I had no idea that this saying was attributed to Confucianism, nor that the emojis were actually based on a Japanese maxim and all have names (Mizaru, Kikazaru, Iwazaru, if you’d like to know). The building is built in a southern Fujin style, much like many other temples we have seen. It is also laid out in a similar fashion, with a central hall containing a tablet with Confucius’ name on it surrounded by peripheral halls dedicated to his disciples and scholars who followed his teachings after his death. Other halls housed museums and rooms that educated visitors on the six arts. One of these halls was a memorial dedicated to Kung Teh-Cheng, the 77th grandson of Confucius. I wonder whether the 78th grandson will carry out the legacy, and whether he will also be remmebered within a shrine in this temple. Many of us also received a work of calligraphy from a teacher in one of the halls. I’m curious if he is paid by donations to the temple or if his work is supported by the Department of Cultural Affairs. I have come across this department on occasion during our cultural visits, as they invest in many of the museums we have visited. Prof. Young mentioned that temples are public property and remain well maintained because they are generally considered integral to Taiwanese culture, and I’ve been learning more on how the government plays a part in maintaining their space. It seems that temples, and by extension religion, are also protected under a more general cultural conservation effort. I’ll have to look more into local indigenous religions and how they are maintained within this syncretic atmosphere.

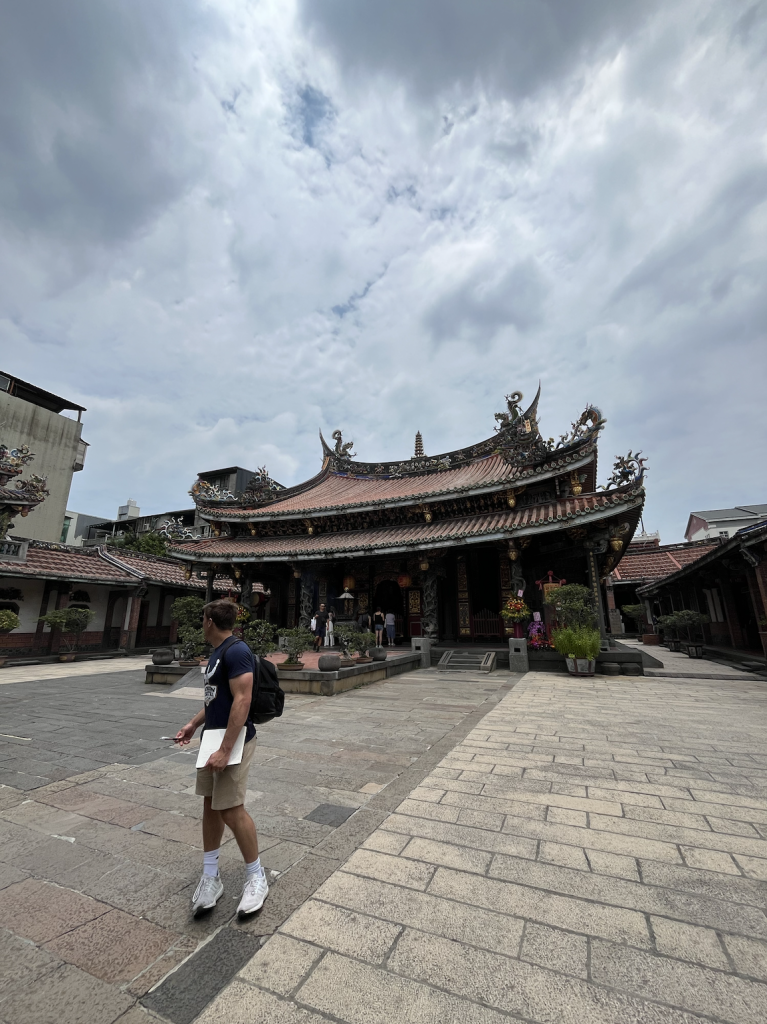

Following this visit, we moved across the street to the Dalongdong Baoan Temple. This temple is dedicated to the god of medicine, Baosheng Dadi. This deity is more regionally specific to Fujin Province, Taiwan, and other parts of Southeast Asia. There is a large furnace just outside the temple, and we got to see the process of burning spirit money in real time. Peter reminded us that people can burn anything, not just money, including paper servants or even technology. This temple also housed many other big shot deities such as Mazu and Shennong, the god of agriculture. The ceilings of this temple were much simpler and had rounded scaffolding, unlike other Daoist temples we’ve seen which are more ornate. There were also many barred windows in this temple, which was a nice change to the construction and allowed viewers to peek into a hall before entering for worship. I noted that this temple, like a couple of others I’ve seen, had a very official, business-like feel to it. There was an office in one wing with a ticekt dispenser outside the door, so I imagine they get large crowds for whatever services they perform. Such temples give people paperwork to fill out. We’ve made wishes before as a class by writing our names and addresses down on a tag that we gave to the temple, so the less cutesy paperwork could be more of a similar thing. It also might be how temples handle larger donations. If you walked through a different hall that seemed to be a workspace for volunteers, there was a larger, more modern Buddhist temple in the back. I mistook it for a business center or hotel, as there were a lot of cars parked outside and it didn’t have the same architecture as the building I was in, so I didn’t get a chance to check it out.

Afterwards, we moved forward in time to see the Peace Park and Presidential Office. This was the first city park in Taipei and also the first museum. The building was originally built to commemorate the first railway built by Japan, and was later the headquarters of the Japanese broadcasting center. It has since been converted into a memorial for the 228 Incident, a.k.a. the 228 Massacre. This incident sparked a period referred to as the White Terror, which was when many people were killed for resisting a nationalist mainland government. We previewed this part of Taiwanese history when visiting the Chiang Kai-Shek memorial, but now we were learning about an important other perspective.

In 1945, many things were happening at the same time: Japan surrendered and left Taiwan, Taiwanese soldiers were returning from Southeast Asia, and nationalists from the mainland were coming in to Taiwan. The first government setup by the Kuomintang (KMT) under Chen Yi was corrupt and barred many Taiwanese from taking government positions. There was also a ban imposed on the sale of alcohol and cigarettes except by the government. On February 28, 1947, a woman was arrested for selling cigarettes, the police were surrounded by Taiwanese passerby, and a shot was fired that killed a bystander watching from one of the buildings. This incited a period of revolt in which a broadcast was made in Japanese from Taipei (the exact building we were in) to rally people to fight against the new government. Both mainlanders and Taiwanese were killed. Part of the exhibit memorialized ordinary people who had little to do with the revolt, but were dragged from their homes and executed under martial law. This was a tragic event for Taiwan that left its mark for many years to come: people were unable to speak of it until martial law was lifted in 1987 and the first democratic election was held a couple years after.

We then walked to see the exterior of the Presidential Office just down the road, which had guards with some pretty serious machine guns outside. Apparently, motorcycles/scooters were once not allowed to drive on the road in front of the office. It was first built to house the Japanese government in 1919 and shifted purpose to be the office of the first democratically elected president in 1996.

We finished up the day with lots of great food! Peter treated us to boba at what has become one of my top three boba places (thank you Peter!!). I also got to try ostensibly award-winning beef noodle soup that was just a handful of blocks down from our hotel, and I’ve discovered I really like beef tripe. I finished up my night after grabbing a cute little chocolate cake from 85 degrees. There is a lot I learned today that I can reflect on, and I hope to continue learning more about Taiwan’s history so I can be better informed on their sociopolitical climate today.